An object "in the making”

The Metaverse constitutes "a leading contemporary communicational, cultural, and social node” (Péquignot J., Roussel F.-G., 2015), towards which companies converge, but also a multitude of sub-ecosystems, organisations, and communities, propelling or being the result of a vast production of knowledge, sometimes at state or supranational level, and of possible funding.

A multi-layered and complex value chain

The convergence of players towards the Metaverse is not simply an effect

of opportunity; it is necessary for its emergence. Behind the "application" layer of the Metaverse, the one that is visible and embodies its uses, there are many technical layers required for it to function. Consider the web for example, which requires network infrastructure (fibre, cables, mobile networks, etc.), hosting infrastructure (cloud), traffic management, secure transactions, digital service visibility (advertising, referencing in search engines and app stores, etc.), digital logistics (downloads) or physical logistics (delivery), and so on.

The Metaverse does not require fundamentally different layers to those of the web, but it does (potentially) reshuffle the cards for players, some of whom have acquired dominant positions. Analysis of the Metaverse must therefore take into account the structuring of its ecosystem of players, digital business models, and the range of usage dynamics that have developed over the last twenty-five years.

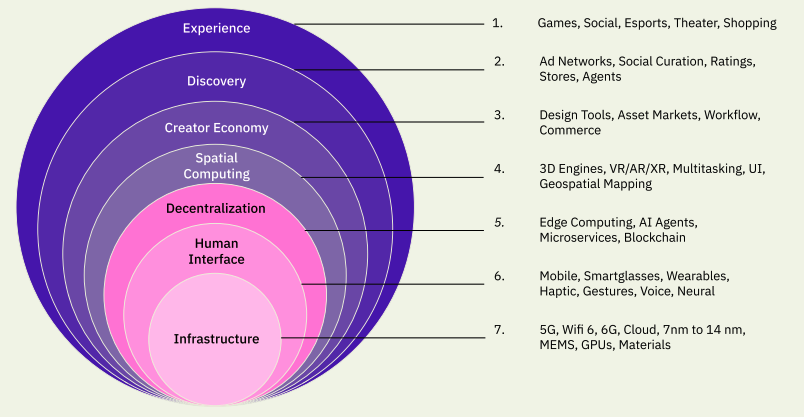

In order to understand the (inter)play of stakeholders and ecosystem structures, we recommend using Jon Radoff’s multi-layered representation of the Metaverse value chain (see diagram hereafter). This representation has been criticised for various reasons (normative risk, restricted vision, aiming to serve its author, etc.), but we believe that this type of illustration nevertheless provides an interesting first heuristic entry point for a fairly simple explanation of stakeholders’ (inter)play and "what is at stake" between the different layers. This type of representation must therefore be considered with caution, and above all in the context of their comparison. It's also in the way the layers interact with each other.

The "Experience" layer (1)

The "Experience" layer represents uses, which cover a very wide range of possibilities depending on the definition we give to the Metaverse.

The "Discovery" layer (2)

The "Discovery" layer refers to the processes and mediations that lead people to discover new experiences (advertising, for example). This layer is already crucial in today's business models, and will be just as crucial in immersive worlds, where the question of how content is organised and accessed will be decisive for the creation of economic value. In this respect, Radoff points out that NFTs [[[A digital token, fungible or not, is a unique digital asset (an avatar, the avatar's head or even an avatar's hair), which is issued and exchangeable on a blockchain network. Tokenisation works as a flexible legal mechanism through which people can define the digital and physical properties of programmed rights. Non-fungible digital tokens can be used for a variety of purposes: membership (closed communities can provide memberships in the form of NFTs to reflect the scarcity of seats in a closed club), loyalty (equivalent to accumulating points), ticketing (a ticket in the form of an NFT guarantees its uniqueness and authenticity), identification of digital or physical goods (NFTs can be attached to physical items to ensure their traceability and transparency), voting, etc.]]] and the sharing of experiences and events in real-time are important drivers of online sociability that will be reinforced in metaverses; social practices that are already well identified and documented in video games and other online virtual worlds.

The "Creator Economy" layer (3)

The "Creator Economy" layer embodies the ease with which anyone can produce and share content (texts, videos, audio, objects, etc.) on the web. In his October 2021 presentation, Mark Zuckerberg mentions the term “creators” nearly forty times (in almost 1 hour 15 minutes), indicating that creators, and artists in particular, will be able to produce and offer their products, services, and experiences directly to their "audience" (or target). As will become clear later on, there are two opposing visions as to how this creator-driven economy should be conceived, between continuing with the predominant existing (centralised) models or more open, decentralised models (cf. “Decentralisation” layer (5) hereafter).

The "Spatial Computing" layer (4)

The "Spatial Computing" layer symbolises, for the author, the increasingly strong hybridisation between the physical world and the simulated world. It includes, for example, motion and voice recognition interfaces and systems, data, or even graphics rendering engines. A large number of players are positioning themselves, or attempting to position themselves, in this layer, including designers of 3D engines such as Unreal Engine (Epic Games) and Unity. They could become powerful players in this value chain through the licences they offer. Under its basic licence, Unreal Engine, the video game engine developed by Epic Games (which is behind Fortnite, among other games), receives a 5% royalty for any game that incorporates Unreal Engine code and generates gross revenue in excess of one million dollars. In this case, the first million dollars is exempt from royalties.

The "Decentralisation" layer (5)

The "Decentralisation" layer diagrammatically refers to two opposing worldviews on how to build the Metaverse, or its various embodiments.

On the one hand, the transposition of current business models, mainly developed since the emergence of the major online platforms. If the Metaverse business models evolve in this direction, metaverse publishers could, based on the model of today's platforms, deploy models in which each user who undertakes a commercial activity is charged a commission, as in today's application shops.

On the other hand, the emergence of one or more decentralised metaverses, based on the Web3 ideology (see “A third path ?”). Certain players already occupy a central position in virtual worlds based on blockchain [[["Blockchain is a technology for storing and transmitting information that is transparent, secure, and operates without a central control body. It is a database that contains the history of all exchanges between its users since its creation. It is secure and distributed: it is shared by its various users, without intermediaries, so that everyone can check the chain’s validity. There are public blockchains, open to all, and private blockchains, where access and use are limited to a certain number of players. A public blockchain can therefore be likened to a public, anonymous, unforgeable accounting ledger. As the mathematician Jean-Paul Delahaye writes, we need to imagine 'a very large notebook, which everyone can read freely and without payment, on which everyone can write, but which is impossible to erase and indestructible’.”

Source : CNIL, «Blockchain»: https://www.cnil.fr/fr/definition/blockchain#:~:text=La%20blockchain%20est%20une%20

technologie,sans%20organe%20central%20de%20contr%C3%B4le]]]. Players such as Ethereum and Polygon, which provide the infrastructure for blockchain and its management, play a pivotal role in these models. The same applies to NFT exchange infrastructures, which are the equivalent of property titles in these spaces. A marketplace such as OpenSea plays a pivotal role.

The "Human Interface" layer (6)

The "Human Interface" layer refers to the terminals and devices through which users access an immersive experience, as well as the type of experience they will be able to have. This layer occupies a very visible part of the debates and speculation around the Metaverse, since while virtual reality/mixed reality headsets are often put forward, others evoke a spectrum ranging from telephones to neuronal interfaces.

The “Infrastructure” layer (7)

The "Infrastructure" layer groups together the technologies (networks, processors, etc.) that "activate our devices, connect them to the networks, and distribute content” (Radoff J., 2021). The Metaverse promises mean that fibre optic infrastructures and mobile networks (5G, 6G...nG) will have to be developed with ever-higher performance.

The value created by services and experiences in the metaverses will depend, for many, on the costs associated with infrastructures and their technical means of access (hence the various “satellite constellation projects and strategic issues at stake between the major web and social networking platforms around the undersea telecommunications cables through which the vast majority of the world's digital data transits). Moreover, as with current digital platform models, many technical and economic players have succeeded in building services that are imposed on websites and applications (hosting, payment, traffic management, advertising, etc.).